“In my mind, paddling Quetico Park represents a perfect canoe trip: life becomes so simple that the stress of the “real” world is left far behind. It can be the kind of trip which you finally begin to understand why wilderness is so important to the human soul.”

The temperature was dropping quickly, wind was whipping in from the southwest, and the sky was looking ominous. The forecast had been right—we were in for a big storm. Time to cinch down the tarp, finish cleaning our dinner dishes, hang our grub pack well out of paw range, turn over and tie down the canoes, and stow and cover the firewood. Tomorrow was a layover basecamp day, and after the last few days of packing, driving, and paddling, I was looking forward to sleeping in and having a leisurely day of fishing and camp life.

Within minutes, the storm moved up across the lake in a wall and hit us with a full frontal assault. Inside my tent, I listened to the rain pour down for a moment or two and then fell into a deep slumber. We had come north seeking wilderness adventure, solitude, and the refreshing pace of a simple, unplugged, natural life. The Quetico was providing all that and more!

This past Spring, my brother, Luke, and I attended a presentation at Canoecopia by Trevor Gibb, the Superintendent of the Quetico Provincial Park Wilderness. Trevor talked about the Quetico’s “northern exposure”—paddling opportunities on the lesser-travelled north end of the park.

The Quetico is located in Ontario, Canada and boasts 1,180,000 acres of woodland with more than 2,000 lakes! The Quetico is slightly larger than the adjoining Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCA) in Minnesota; however, it sees only 10% as many visitors, most of whom paddle in from the Quetico's southern boundary. For anyone unfamiliar with the BWCA or Quetico, these vast protected wilderness areas are undeveloped; no roads, no park shelters, no motorized travel. To travel through this country, you paddle your canoe from lake to lake, carrying it—and your gear—over ancient portage trails that connect the bodies of water.

The idea of putting together a canoe voyage for a group of friends that offered isolated wilderness and didn’t require everyone in the group to have advanced whitewater paddling skills was very appealing. Luke and I immediately started planning our Quetico trip on the road home from Canoecopia.

The Heart of the Continent

On the road, by foot, and with paddle in hand, our Quetico trip perfectly circumvented an area National Geographic recently declared as “The Heart of the Continent.” Our plan for this trip was to explore this great region, take in its wild beauty, and introduce a few newcomers in the crew to wilderness travel, while helping them develop the skills needed to further explore the northwoods. And, of course, to have a really great time with a group of good friends!

Our view while camping on Batchewaung Lake in the Quetico.

This trip was a near-perfect sample of wilderness canoeing—and all without any sign of, or intrusion from, modern life:

We had one particularly mosquito-infested camp, but the bugs were pretty mild overall; I never even broke out the insect repellent.

There was one powerful storm with wind and rain coming down so hard that an atomized mist was coming through the mesh door of our tent as rain drops smashed on the rocky ground, but all other days were nothing but endless blue skies.

We paddled across miles of beautiful, massive lakes.

We saw abundant wildlife, including a moose and a bear on the park's edge, and bald eagles frequently soared over our camp.

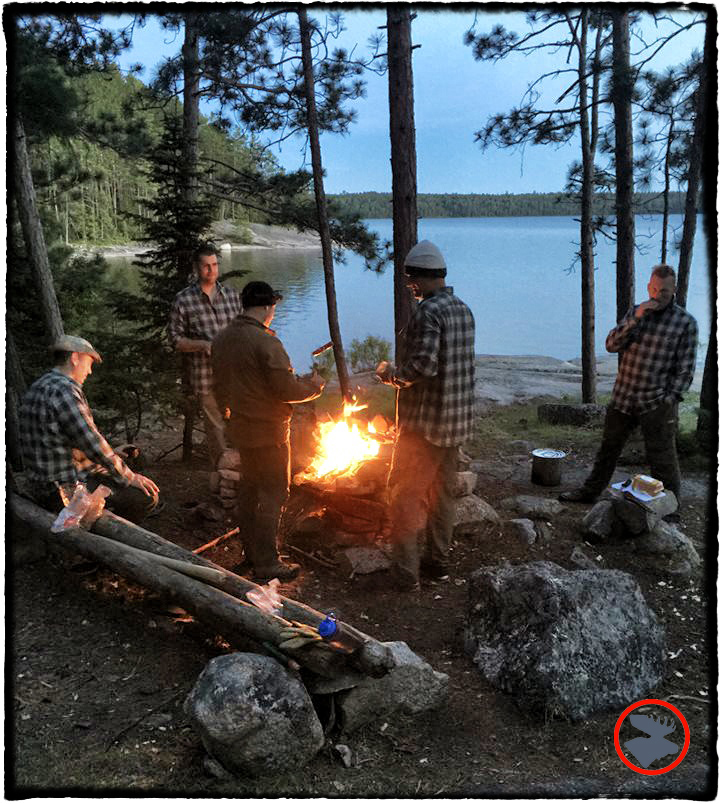

We caught huge fish and ate massive quantities of delicious food that we cooked over fire.

We chopped, sawed, and split wood to feed fires for cooking.

We enjoyed panoramic sunsets while listening to loons calling.

We laughed long and hard into the night, while watching shooting stars and sparks pop and dance out of the campfire.

On top of all that, our route only required ONE (yes, just one!) portage, and I’d rate it at moderate difficulty. Hardcore canoeists have come up with many ways to justify the benefits of portaging:

It quickly separates you from the crowd

The great historical connection to the native and fur trade travelers who crossed the same paths hundreds of years earlier

The fishing is better on the other side

The great sense of accomplishment that comes with completing a hard trip

Paddling solo in the Quetico.

I think there is some validity to each of these points, and I look back fondly on many trips filled with challenging portages (including one cliff face on the Kopka River which required climbing ropes to lower our canoes and gear over!). But, if I'm being honest, portaging isn't all rainbows and lollipops. Often, it's damn hard work. If you can have the wilderness experience you're looking for without the extra pain and suffering that often accompanies portaging, why not go for it?

The Route

Our route—our entire trip, really—was pretty simple. And although it was simple, our route still provided the wilderness experience we were seeking, including plenty of solitude. In fact, we only saw a few other paddlers—far fewer than the amount of paddlers I typically encounter in the BWCA at this time of year. Below, you can see where we put in on the north side of Nym Lake, and our campsites for each night (1, 2, 3, and 4).

Venturing into the Quetico is a lot like a BWCA trip, with only a few differences:

Doug Chapman's Outfitter shop.

You have to cross the U.S./Canadian border, unless you're Canadian, eh?

You won't find any officially designated campsites, fire grates, or thunder boxes in the Quetico, unlike the BWCA; however, most of the ideal sites are well established and there is no reason to whack out a new one.

You need to incorporate at least one Tim Horton’s stop into your schedule.

Doug Chapman’s outfitter shop (located just outside of Atikokan, Ontario) supplied our crew with Souris River Kevlar "Quetico" canoes. These canoes are light and sleek. Doug was very helpful in securing permits, offering route suggestions, and giving other trip advice. I opted to paddle my own old 16’ Wenonah "Flambeau" Royalex river canoe solo, which was fun, but on the big windy lakes, keeping up with the tandem crews required some effort on my part. Learning to paddle a standard tandem canoe solo, or "Canadian Style," in a variety of conditions has greatly increased my canoeing range and enjoyment. I highly recommend studying Bill Mason's excellent books and videos on the subject!

“Will you boys be doing some fishing then? Good, good, we’ve got walleye dying of old age in there!”

Our Quetico crew ready to paddle! (L-r: Silvers, Griffin, Giant Cloquet Voyaguer, Luke, Bartek, Clay, and Wilke)

DAY 1

Heading north out of the Twin Cities, we stopped in Cloquet, MN to fuel up at the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed gas station and check out the giant voyageur statue. With the hammer down for another hour, we rolled into the Iron Range and made a pit stop at the Sawmill Saloon & Restaurant in Virginia for a few pounds of wings, nachos, pizza, and beer. Great start to any outdoor adventure! Another two hours on the road and we made it to International Falls, MN where we spent the night.

DAY 2

Luke leading on the portage to Batchewaung Lake.

We crossed the border and drove two more hours to reach Atitkokan, Ontario. Our put-in point was on Nym Lake, just east of Atikokan. After our check-in at the ranger station, some last-minute shopping, and rearranging gear and packs at the outfitter's shop, we were on the water by early afternoon. We crossed Nym and portaged into Batchewaung Lake, where we sought out the ranger-endorsed "5-Star" campsite on the peninsula on the northeast side of Batchewaung Lake. Bartek, who grew up in Warsaw, Poland, had brought a load of goods from his local Polish deli in Chicago, so we went to work on the kielbasa, bread, and 5-pound block of cheese he'd brought for dinner, followed up with freshly baked bannock, Polish cherry cordial, and cookies in the reflector oven!

DAY 3

The next morning began with a brotherly dust-up between Luke and I over the exact formula to use in making the camp coffee. I have to admit that Luke did have a good point: the traditional woodsman's ratio, which I advocated, of "a handful [of grounds] for each man and one for the pot" really didn't make sense. The grounds should be measured according to the amount of water in the pot, but I wasn't about to allow for some sissy show of measuring teaspoons of grounds and counting ounces of water!

Luke decided the best way to show me up was to start tossing handfuls of grounds into the pot while loudly calling out each man's name. We don't use a percolator, so It was going to take some aggressive action to separate the mass of grounds and leave us with drinkable coffee. Several vigorous full arm revolutions (check out the video below), and we were able to enjoy some hot and strong cowboy coffee to get us going!

After throwing in a handful of grounds for each man—and one for the pot—I swung the coffee pot to allow the grounds to settle. Camp coffee brewed cowboy style in the Quetico!

After the great coffee debate had settled, we packed up our canoes and paddled along the western shore of Batchewaung Lake and entered the channel to travel down through Little Batchewaung Bay, then through Batchewaung Bay, and finally into Pickerel Narrows. The crew pushed through stiff headwinds from the southwest throughout most of the day.

Initially, I planned on continuing into either Maria Lake or further into Pickerel; but, rain was forecast, the skies were clouding up, and the temperature was dropping. With bad weather clearly moving in quickly, we opted to make camp on the northwest side of Pickerel Narrows, directly across from the ominously named “Mosquito Point.” We battened down the hatches and slept soundly through a full night of pouring rain.

DAY 4

Hudson Bay Bread slathered in Nutella made a delicious, high-powered, ready-to-eat breakfast item on our drizzly morning.

Our fourth day started off rainy, but cleared up by midday. Given our schedule, we'd planned this day to be a layover day, so we stayed put and spent the day fishing, swimming, and learning wilderness skills.

This site was a bit small for our group, and it was dense and swampy just behind camp, but the site did have a large, sloping rock face on the waterfront, which was a great area to hang out and watch the lake and the night sky.

In between fishing and skills sessions, we drank plenty of coffee, ate a lot of Hudson Bay Bread (check out our recipe here), fried fish, bacon, bannock, and enjoyed roasted pork tenderloin for dinner.

Clay was our most experienced and enthusiastic fisherman, and under his tutelage, tenderfeet Wilke, Silvers, and Bartek landed some monsters!

DAY 5

At the crack of dawn, give or take, we retraced our route and paddled back up the Bachewaung chain and camped on the point of the long finger sticking up into Batchewaung Lake (check out the map photo above). This was the best site yet, however, it seemed the mosquitos hadn't heard the bit about them not liking high, dry, windy points, and they came after us in full force. Still, we saw a stunning sunset, which we enjoyed while dining on jambalaya, mac and cheese, and more cookies baked in the reflector oven.

DAY 6

Our last full day on the water was spent paddling back out through Batchewaung Lake, portaging to Nym Lake, and then paddling back to our vehicles. Another great day of paddling the Quetico!

After pulling off the water and packing up, we continued our trip, traveling east on the Trans-Canada Highway for two hours to Thunder Bay, Ontario, where we crossed into the U.S. of A. and spent the night in Grand Marias, MN. We stopped to see the fur trade monument at Grand Portgage and had the traditional post-canoe trip pizza feed at Sven and Ole's in Grand Marais. After dinner, we saw a dramatic display of the northern lights over Lake Superior!

Sundown in the Quetcio

Gooseberry Falls in Gooseberry Falls State Park, MN.

DAY 7

We came back into the U.S. through Grand Marais so we'd have the opportunity to experience the wonderfully-scenic drive along the north shore of Lake Superior with the Sawtooth Mountains, the rocky coast, cliffs, waterfalls, and rugged hiking trails. After breakfast in Grand Marais, we walked over to the North House Folk school, where we visited with some friends, were treated to a fire by hand drill demo, and got to check out a recently finished birchbark canoe.

The remainder of the day, we spent driving south along Route 61, stopping to hike along the Cascade River and Temperance River trails and visiting Gooseberry Falls on the way back to Minneapolis. It was a fantastic end to a memorable trip in the isolated wilderness of the Quetico.

Lessons in the Bush

While this trip wasn’t specifically designed as a training course, we did take time to discuss and practice several key wilderness skills:

Our canoe crew crossing Pickerel Narrows in the Quetico.

Paddling Technique. A few of the guys in the crew had never paddled before. We met for some pre-trip practice sessions and continued refinement in the Quetico. The primary focus for this lake country trip was to become competent with the “J” stroke in the stern, handling wind and waves, and decision making when facing open crossing on large bodies of water. The lakes on the north end of the Quetico are really big and really windy, so you want to feel comfortable with basic canoeing skills before heading out.

Bartek practicing safe axe handling and splitting wood to feed the fire.

Axemanship. Everyone on the trip was outfitted with a Mora fixed-blade knife and a Bahco folding saw to aid in preparing firewood and campcraft. I also brought a ¾-sized Boys axe and demonstrated safe and efficient axe technique. After the downpour the night before, I focused on showing the crew how to split wet wood to reach its dry core. This allowed us to maintain clean, bright, hot cooking fires, instead of blowing on and hoping that a soggy pile of sticks would suddenly burst into flames and fry our fish and bacon. I brought an older restored Plumb axe, which has softer steel than the hard-edged Gransfors Bruks axe, making it more likely to roll and less likely to chip if the blade hits a rock. In the Quetico, you're camping on the “Canadian Shield,” which is all rock, with sparse layers of dirt on top, so slightly softer steel can be easier to resharpen.

Navigation. We discussed taking bearings, orienting a map, route finding through deceptive bays and past islands and points, and the importance of “aiming off” when traveling toward a portage trail or campsite.

Knots and Rigging. Each day, we needed to set up the tarp and tents, hang our bear bag, and generally get camp shipshape. To do this, we put a number of knots to work, including some of my favorites like the Timber hitch, taut-line hitch, trucker's hitch, bowline, prussic, and jam knot. Being able to tie knots mid-line and “slippery,” or "quick-release," saved a lot of time and effort setting up and taking things down in camp.

Bushcraft and Pioneering Skills. With no existing fire grates in the Quetico, we brought a standard campfire grate to use for cooking. It worked well for awhile, but when it really got heated over the fire, it soon buckled under the weight of the large stockpot we used to boil water. We worked around the buckled grate for awhile by partially supporting the pot on stones, but it soon suffered a critical failure and caved in. So, we lashed together a large cooking fire tripod rig and carved pot hooks out of dead wood. This was a much more useful camp cooking set up than the mid-sized grate anyway.

We constructed a fire tripod rig and carved pot hooks out of dead wood to boil water and cook our meals.

Everything we cooked in the Quetico, from basic toasted snacks to multiple course meals and baked desserts, was on the fire. We ate well. Probably too well.

Fire Lighting. This was a key daily task, rain or shine! We covered the basics of fire lighting, as well as feather stick making and the tinder bundle method of lighting fires in wet and windy conditions.

Campfire Cooking. All our meals were prepared over an open fire, which was new to a few guys on the crew, but with the incentive of hot coffee in the morning or hot and gooey cookies in the evening, the guys very quickly gained an understanding of how to build, maintain, and manage cooking fires. They fried, roasted, baked, boiled, and grilled, and the food was delicious!

If fire danger had been high, I would've brought a stove. On this particular trip though, fire danger was low, so we took the opportunity to work on and enjoy our cooking-over-a-fire skills.

Even though the Quetico is heavily forested, firewood can be picked over around popular campsites. We never had a problem finding firewood, but to do so, sometimes we had to take a short paddle down the shore and go a few steps up into the woods. Once there, we were tangled up in a gridlock of downed dead wood ready to be taken back to camp.

Griffin demonstrating a patient assessment on Luke.

First Aid. One of the guys in the crew, Griffin, is a S.W.A.T. team member, paramedic, and Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) Instructor. He took us through the TCCC protocol and covered basic responses for the types of major trauma that might be encountered in the wilderness, such as tourniquet usage, pneumothorax, spinal and head injuries, and patient transport techniques.

Gear Put to the Test

In addition to the tried and true items on my regular packing list, I put a few new gear items to the test on this run, including two excellent products from Minnesota-based shops:

My Kondos Outdoors insulated food pack kept our food cold and was comfortable to carry.

Kondos Outdoors Insulated Food Pack. This was a wonderful addition and came highly recommended from my friends at Northern Tier High Adventure BSA. The Kondos pack is very sturdy, was comfortable to carry, and helped keep our food cool. I had a few frozen items (e.g., pork loins, a carton of egg beaters, lots of chocolate, and Hudson Bay Bread), and several refrigerated items (e.g., cheese, sausages, and eggs) in the Kondos pack, and they were all kept cool. The pack design also makes it easy to hang, and I'd like to point out to my Mainer friends, it portages much easier than a cooler on a tumpline! The Kondos pack will become a regular on my trips, even day trips with the family to keep picnic items cold.

Cooke Custom Sewing (CCS) Silnylon Tarp. Although I had used my Cooke tarp a couple times before, this trip was the first time I used it in high winds and driving rain. With the monstrous downpour that blew through our second night on the trail, I was relieved to have the band of webbing around the edge of the tarp and the many reinforced tie-out points of this heavily fortified tarp. This CCS silnylon tarp is a large at 10' x 14', but the 1.9 oz silnylon material makes it lightweight (2 lb, 10 oz) and compacts easily. CCS does make an even lighter 1.1 oz version if you're counting the ounces. My silnylon tarp didn’t begin to show signs of wetting through, as I’ve seen on many other treated nylon products. Dan Cooke's experience living out of a pack in the north really shines through and was incorporated well into this great product!

The crew in their Eddie Bauer Expedition Flannel shirts.

Eddie Bauer Expedition Flannel Shirt. I know, I know, you're thinking "Mall Mountaineer!" But, Eddie Bauer is making a serious effort to crank out some solid outdoor gear again, and this Expedition Flannel shirt is spot on. These shirts look and feel like your traditional flannel shirt, but they're made of hollow core poly material, which is light, warm, feels great, and is hydrophobic instead of typical cotton flannel that becomes soggy and useless with the first drops of water. I really like the traditional look of these shirts and the button front and flap pockets make it much more functional and versatile than typical pullover synthetic clothing. One word of caution: like most synthetics, these shirts will melt. We were around fires the whole time without incident, but I have a large spark hole from another trip in mine. Overall, these shirts make a great warm layer on a canoe trip!

NOTE: Eddie Bauer carries tall sizes—which actually fit tall guys—and this was important for this BMP "Sons of Bunyan" expedition because the group consisted of a bunch of my volleyball buddies, only one of whom was under 6' 4".

paddle the Quetico!

With our relatively short schedule, and a desire to spend time fishing and enjoying camp life, we really only scratched the surface of this massive Canadian park. At the same time, the crew agreed that we had immersed ourselves in an awe-inspiring wilderness—and we were only one portage into the Quetico!

If you're seeking wilderness, and your skills are up to it, give strong consideration to the Quetico. Your route options are almost limitless, and you’ll find incredible beauty, peacefulness, and freedom.

Looking for an outdoor adventure that isn't the Boundary Waters (BWCAW)? Check out six of our favorite upper Great Lakes region canoe camping destinations!