In the hands of a skilled user, the axe can be an incredibly valuable tool on the trail and in camp.

I'm an axe fan, and I use a few kinds, ranging from a tiny pocket hatchet to a large splitting axe. If space and weight aren't too much of a concern, such as when I'm traveling by canoe or snowshoe and sled, I often choose a 3/4-sized "boys axe," especially if I'm in heavily forested areas. If I'm cold weather base camped in the hardwoods of the Mississippi River valley and planning on a decent-sized fire, the big splitter will likely make the trip. On a warm Summer trip, with plenty of dry wood around? Chances are even then a small hatchet may still get tossed in the bottom of the pack.

For me, the axe's primary use is to split wood for the campfire to expose the dry heart wood. This can be a lifesaver in the Winter northwoods or during wet conditions, but is also quite helpful if you're trying to make a campfire out of the rotten slabs of wood sold in bundles at your local state park campground. In other instances, like when I'm backpacking, I rarely carry an axe; mainly due to the weight, but also because in a lot of the mountains where I backpack, it wouldn't be appropriate to cut down the sparse woods.

My thoughts about axes are different than many outdoor organizations, however, because many organizations steer away from traditional bushcraft techniques using a knife or axe due to safety and environmental concerns. Instead, those organizations developed self-contained modes of travel relying on modern stoves, clothing, and shelters. This is great for high-use areas or fragile environments where minimal impact is important. However, if that self-contained system fails, or if you're traveling off trail in truly rough country, basic bushcraft skills and an axe can save the day. While traveling down the Kopka River in Ontario, my small old Norlund hatchet and a folding saw were crucial in helping fashion two crutches for a friend who'd badly hurt his foot in rapids.

Quality vs. Quantity

New high-quality axes aren't cheap though. Cheap and junky axes are cheap. With prices ranging from $100 - $200 or more for a new high-end model, your axe should be a thoughtful purchase.

Rather than buying an axe new, a less expensive route is garage or estate sales. Although any axe found at these sales is likely to require restoration, it'll be much cheaper than buying the axe new. (Note: My advice is to stay away from antique shops. The axes I've found at those shops are often really beat up, overpriced, and targeted toward buyers looking for rustic decor rather than actual use.) You could try looking on ebay, but the vintage axe market has heated up there and that is the free market at its best. With full transparency and open bidding amongst axe lovers the world over, you'll pay a pretty penny for quality pieces. I bought the Plumb axe mentioned below for $3 at a garage sale, and I've seen similar models trade on ebay for $50-$75 or more. If you happen to find an axe at a garage sale, I'm guessing it'll be covered in rust and have a loose and splintered handle. If the head hasn't been abused too much and the steel is solid underneath, the axe can often be brought back to life. Check out the two axes I found at garage sales--the before and after is pretty incredible.

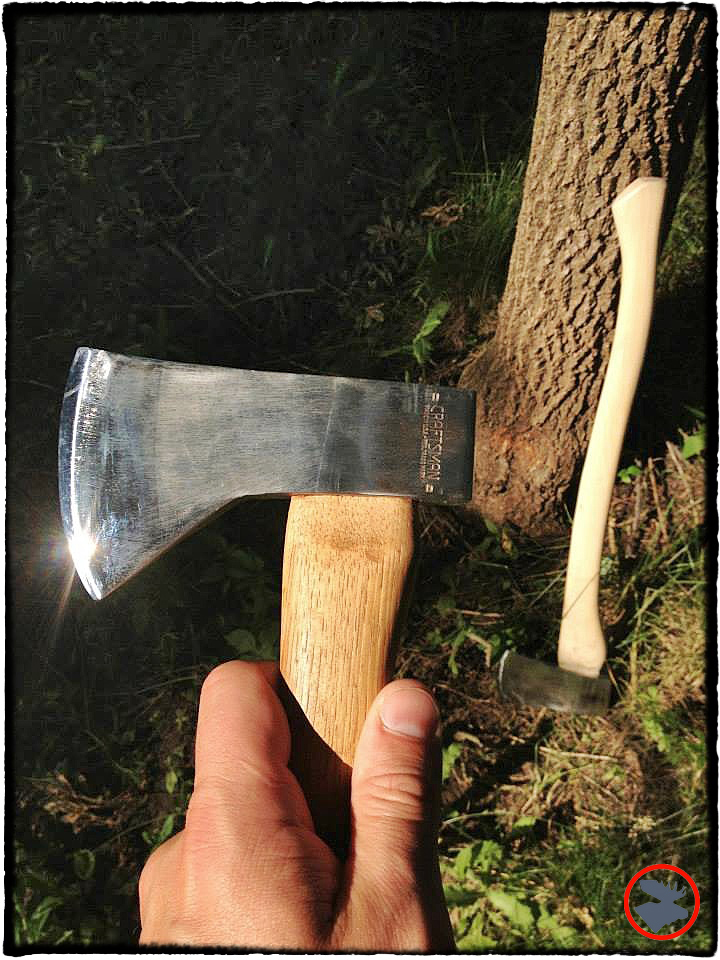

Two axes I found at garage sales before their restoration. On the left, a Craftsman, and on the right, a Plumb.

The Find

The quality of an axe is similar to the price of an axe: it can range from really low to really high. Being the sort of individual who likes to find a good deal, I was feeling like I hit the jackpot last Summer when I found a beat up Plumb 3/4 boy's axe for $3 and a Craftsman hand axe for $2 at local garage sales.

Plumb has made a lot of "Official Boy Scout" axes, and I'd seen how fine some of these tools can be with proper care, so when I ran into this one--beat up as it was--I snatched it up.

Rob Kesselring once told me that he thought old Craftsman axes can be pretty good. The Craftsman I found was quite small and light with a Hudson Bay pattern head. It's almost like a tomahawk-hatchet hybrid. When I tested it, I heard the steel ring underneath all the rust, paint, and gooey stickers, and the head was stamped, so I thought the metal might be worth the $2.

The Plumb axe head was rough with surface rust and light pitting. The edge was in bad shape and unevenly ground. After further inspection, I called the handle a complete loss. Rotten and splintering around the eye, there was no way I could reset it. The good news was the eye and poll were in good shape.

No sense in letting a potential good axe waste away even more, so I set out to get these two pieces of garage sale gold back in action.

The Fix

Craftsman

The head on the Craftsman would be an easy tune up, but the handle was a problem. It was smaller than normal, so finding a replacement would be difficult, and truthfully, I'm not sure I have the skill to carve a handle that would fit the small eye. I ran over to my boy Beau's shop--Beaumont's Quality Tools in Minneapolis--to show him my find. Beau groaned when I walked in the door. After all, the name of his shop says “Quality Tools,” and I keep bringing him junk like this axe. But, after a short inspection, Beau agreed to take on the project. I thought the handle was trashed for sure, but he wanted to try and save it; he admired the tight-grained hickory under the paint spatters. In addition to working on the handle, Beau is able to use his pro grinding tools to put on an edge that would make a samurai drool!

Craftsman axe head before restoration. While it looks cruddy, the sticker, original paint, and lack of wear on the poll and bit show that it probably wasn't used much.

Really unsafe temporary fix someone gave this axe head.

Beau calls me within 24 hours of dropping it off. “Hatchet is ready. I think you'll like it.” Does a bear like honey? Holy Horace Kephart's ghost! This turned out to be one sweet little cheese axe!

The blade was scary sharp. Note the temper line a quarter of the way back on the blade. Harder temper on the steel from there forward to take an edge. This sucker sliced paper with ease when I picked it up. Also did a nice job shaving feather sticks. Since the edge is slightly convex, it's not quite as easy as with a knife holding a scandi grind edge, but it does the job.

The handle is a little skinny for my liking, so I may wrap the bottom to thicken it up, but look at what Beau did with that handle!

Fully restored Craftsman axe!

The head is now solid and safe to use.

From the handle to the head, this axe looks and feels brand new.

The head is also nice and tight now. Beau pulled out the random nails and screws that someone had put in for a temporary fix, carved away the cruddy wood, and put in wooden and steel wedges. Obviously, this isn't a tool for heavy chopping, but it should be just the thing for more refined camp tasks, like chopping avocados for guacamole. Alright, fine, that's my brother’s routine—I won’t take credit for that one. The Hudson Bay design let's you choke up and get your hand very close to the centerline of your cut when you are carving with a push stroke, allowing you to take on many knife tasks or use it like an ulu. But since there’s not as much metal around the handle, the head design can work loose, so it shouldn't be used for a ton of splitting.

Plumb

With the Plumb, I had to do some pre-work to clean it up before I could even bring it to Beau to work on with his professional grinding tools. I put some elbow grease into scraping rust and crud off the blade, then soaked it in Coke for a few days to eat away at more of the corrosion. This, of course, raised my investment in the project by another $1 (used a few cans of Coke), but it seemed worth it.

Plumb axe head I found at a garage sale. Solid metal, but it needed some serious clean up.

I soaked the axe head in Coke to help get rid of the corrosion.

With the Plumb handle shot, I had to find a new one. Most axe handles suck. Mills Fleet Farm had some nice replacement handles with quality hickory, a good shape, and nice waxed finish. It still took quite a bit of digging through the bin to find one that was a good fit and had the grain running parallel to the head to prevent splitting, but eventually I found two decent handles and bought them both so I'd have a spare on hand. (I took a winter survival course with Mors Kochanski, and remembered his advice of "always be an axe handle ahead.")

Axe handle options at Mills Fleet Farm (MFF). MFF has a surprisingly good selection of axe handles.

From there, I was back to Beaumont's Quality Tools. Beau performed his magic again, grinding and polishing the head. I then took the stone and strop to it to give it a finished edge. You can certainly do the rough edge work, taking out chips, and thinning the head yourself with files (I've done this with old Sager and Norlund axes), but I've become a real fan of Beau's work. He's able to do the job quickly and with great results.

And the Plumb ended up being sharp enough to shave a sleeping mouse! It's rewarding working with the Plumb steel. It really responds to the Lansky dual-sided puck stone. Some of the high-end Swedish axes are so hard, I find them a bit frustrating to sharpen.

With a nice sheath from Harry J. Epstein, this tool is ready for the trail! This axe is well suited for canoe, winter, or base camp purposes. It's a bit longer and heavier than the Swedish limbing axes, and I think the fuller convex bit splits wood better. Combined with a good saw for bucking the wood into splittable lengths, this will keep Bull Moose Patrol warm and toasty all night!

Sharpening my like-new Plumb axe with a Lansky dual-sided puck stone.

The sheath is from Harry J. Epstein, and it fits the Plumb axe perfectly!

The Finish

Both the Plumb and the Craftsman worked well for my favorite kindling technique. None of this Jenga-esque balancing the stick on end, quickly swinging at the toppling stick, or your pointer finger holding it up, and then deflecting the short handled axe into your shin. A short chop onto the side of the small stick is all that's needed to get the split. Kneeling so that any deflection will go into the ground, not my flesh. It's true, check the geometry. Using a nice chopping block to protect the blade from dirt or rocks, and there’s no need for a flat chopping block with this approach.

Chopping kindling with the Craftsman axe. My preferred splitting technique with a hand axe. Safer and quicker than standing each piece on end.

The Hudson's Bay head on this little axe lets you choke up for great control. All fleshy cuttable body parts out of the way of the blade and its follow through. Leaning in with a stiff arm and body weight seems to work better for carving than pushing from the elbow.

Sharp! Easily making feather sticks for the fire with the Craftsman hatchet. You won't be able to put this kind of edge on most axes found on hardware store shelves today.

This video from the U.S. Forest Service details how to restore an axe. It's a great presentation with a lot of helpful information for anyone restoring an axe for the first time.

If you want to learn more about the creation of high-quality axes, check out this video shot by Peter Vogt in 1965 in Oakland, Maine (an area once well-known for making some of the highest quality axes). Mr. Vogt features the Emerson Stevens shop--the last axe production company in Oakland, Maine--and provides a unique view of axe creation.