A Legend

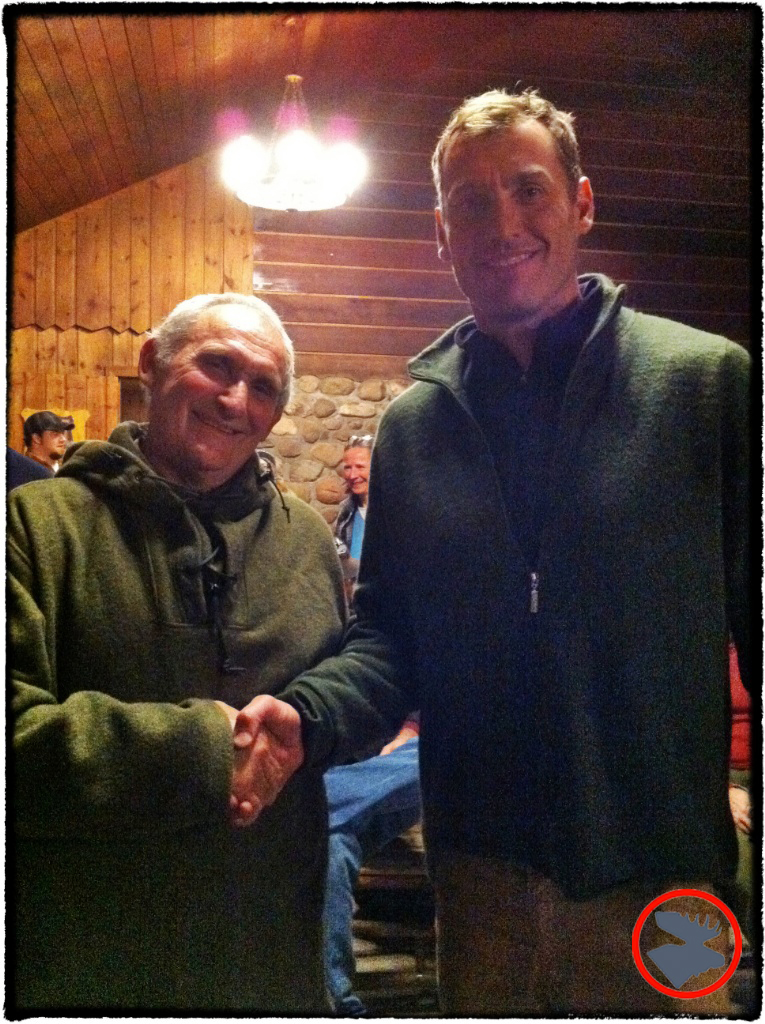

Mors Kochanski and I at Winter Camping Symposium 2012.

Mors Kochanski is a legend in the outdoor survival world.

Mors' knowledge is exhaustive and his experience is beyond impressive. He has spent a lifetime testing and refining survival techniques in the northern wilderness, as well as advanced bushcraft skills that can allow one to live comfortably in the wilderness with the materials they find in the woods around them. He taught these survival skills to the Canadian Air Force, at the University of Alberta, as well as running his own private course (Karamat Wilderness Ways). His knowledge of the boreal forest region—the terrain, the plant life, and the animals—is highly advanced. He's published a number of books and DVDs, instructional pamplets, written numerous articles, was editor of the "Albert Wilderness Arts & Recreation" magazine, created a YouTube channel with hours of instructional video, and his flagship book, Bushcraft, is a staple in any northern outdoorsman's library.

Studying with Mors

Several years after first reading Mors' work, I was thrilled to have the opportunity to take Winter survival and bushcraft classes from Mors through the North House Folk School in Grand Marais, Minnesota. Spending the Winter nights sleeping in a lean-to in front of a long log fire and learning from Mors in the frozen deep northwoods was fantastic! The next year, I worked with Mors to set up a Wilderness Survival School for the Northern Star (Minneapolis-St. Paul) Council of the Boy Scouts as a fundraiser for Eagle Scout college scholarships, and later in the year, hung out with him again at the Winter Camping Symposium (this event has become upper Midwest top bushcraft meet-up!).

I've taken several of Mors' classes, read all of his books, and watched his DVDs. His knowledge and passion for the outdoors and wilderness skills has made him one of my favorite mentors.

I've learned a lot from Mors. In fact, narrowing this list down to 10 items was quite difficult, and I'm leaving out many important concepts. Rather than just throwing out a handful of interesting primitive techniques or pictures of cool "survival" knives, I think it's important to understand the objective: stay alive!

Mors repeatedly stressed a couple of key fundamental points:

Inform someone who is responsible about your trip route and your expected return. This trip plan should trigger rescue in the event of an emergency and will give reassurance that help is on the way!

Learn how to prevent dying of "exposure," which is typically a combination of fatigue, dehydration, and hypothermia. Mors' techniques and gear recommendations are largely based on attaining sleep, maintaining warmth, staying hydrated, and signaling for rescue.

With those concepts in mind, here are the top 10 survival techniques I learned from Mors Kochanski.

Top 10 Survival Concepts

1. Learn Specific, Applicable Knowledge

“The more you know, the less you carry.”

There are many survival books that cover survival in the mountains, desert, forest, ocean, jungle—you name it—all of which offer general advice. When you listen to Mors or read his books, the first thing you notice is that he's different. He is an expert in his environment, the boreal forest, and he provides highly detailed instruction and specifc advice, so you can actually survive there. Everything he teaches, he's tested in the elements—repeatedly—and it works.

2. Super Shelter

A Mors Kochanski original, the "Super Shelter" is a dramatic upgrade to the classic pine bough lean-to you see in nearly every survival manual. I've spent several nights sleeping in Super Shelters in northern Minnesota during the Winter and will attest that they can be quite comfy.

Super Shelter that I built in Superior National Forest.

Super Shelters feature a raised bench covered with conifer boughs that double as a bed, a back wall lined with a reflective Mylar space blanket, and a clear plastic sheet that hangs down the front. These Super Shelter components, coupled with an appropriate fire (placed "one large step away" and built with logs "an arm's span long") create a bubble of warm air high and dry off the ground. Not only does the clear plastic create a greenhouse effect with the fire's warming rays, it prevents you from choking on smoke all night, as is typically the case with open front lean-tos. Depending on the outside temps and whether it's a sunny day, the Super Shelter may even provide adequate warmth in the daytime from the sun's rays.

You need a minimal amount of gear in your survival kit to construct a Super Shelter: a 2-ml plastic sheet, a reflective space blanket, cordage, and a bushcraft knife. Additional covering material, such as a tarp, and a saw will help create a first rate home. Once you understand the Super Shelter design principles, they're reasonably quick to construct, making them arguably one of the best survival shelter options available in the northwoods.

3. Eat?

To chow or not to chow, that is the question. Fast and conserve energy? Spend energy hunting and gathering? Mors introduced this trade-off to me. The idea of not eating had never crossed my mind. I'd assumed it would make sense to eat whatever small amount is available (e.g., bugs, mushrooms (yuck), and edible plants) in a survival situation, which is what you typically see promoted by survival gurus. Mors has a different view. He contends that you have to consume more energy than you expend in hunting and gathering, and hit a daily baseline of 1,200 calories with 500 of those calories coming from carbohydrates. If you can't consume that many calories, you're better off letting your body go into fasting mode.

I will admit I still struggle with the fasting concept. From my own experience, I know how having some high-calorie trail food on hand can provide a needed energy boost if you're running late and have a to push through a few more miles. Food is also vital in generating body heat when you're out in the deep cold. When we're Winter camping in the Boundary Waters in January, if you don't eat enough, you get cold quickly!

Mors does suggest carrying prunes or OXO soup cubes for short-term energy in your survival kit. He also has advice on trapping and primitive fishing techniques, but he considers those advanced skills, not likely to be necessary in most survival situations. The knowledge that you can potentially live 40 days without food is somewhat comforting, although I have no desire to give it a try! I prefer to pack a few survival PB&Js and some emergency Snickers.

4. Drink!

Staying hydrated—especially in cold weather when you may not feel like, or think you're dehydrated—cannot be understated.

Your pack should contain a decent-sized pot so you can boil water. One of the most difficult items to fabricate in the wilderness is a pot to boil water. Yes, you can potentially make a folded bark container, or put hot rocks in a hollowed out log, but it is difficult and time consuming. Many filters will freeze in severe cold and chemicals won't dissolve properly. With a metal pot and a fire, you can warm the water and melt snow, which is a big advantage in cold weather survival.

5. Sleep!

Mors puts great emphasis on the importance of getting sleep in order to survive. He cites studies that show sleepless nights can slow your brain function to the same degree as alcohol bingeing. Your ability to think through challenging situations becomes murky, and your mental attitude and the all-important will to live crumble.

While other survival books will show shelters, Mors is the first instructor I've heard specifically hammer home the importance of sleep for ongoing function. In the cold northwoods, sleep will be very difficult to obtain without understanding other survival skills and principles. A well-constructed Super Shelter becomes a wilderness resort and allows for great sleep. A quinzhee (snow mound shelter) can maintain an inside temperature just below freezing (which may be 40 degrees warmer than the outside air!), simply with proper design and body heat. Mors has said that in the deep cold, it is often easier to sleep in the sunlight during the day and tend a large, warm fire at night.

6. Clothing

"You should be able to live three days at -40C/F with just the clothes on your back. That is how you know that you've adequately prepared for the Winter wilderness."

Pretty much everyone I know, myself included, routinely fails this test. I've heard Mors say many times that "A down jacket stuffed in a coffee can (which doubles as a pot for boiling water) makes a pretty good survival kit." If you do a search for Mors online, you'll find endless debates about his knife, axe, and fire recommendations—the exciting stuff—but if you take a Winter survival course from Mors, you'll learn that he spends a great deal of time upfront talking about clothing and the science of dressing for Winter wilderness. Clothing is shelter that you wear and your first line of defense!

Although BMP shirt alone is not enough to help you survive at -40C/F for three days, we think even Mors would agree that it certainly is a comfortable and practical outdoor option. Photo credits: Dragan Uzelac of Niko Wilderness Education and Patrick Rollins of Randall's Adventure and Training.

7. Fire Lighting

I thought I had solid fire-lighting skills. In my old Boy Scout Troop, we always strived for "one-match fires," and my brother and I have long carried on this tradition, even while enduring jeers from others of "just pour some gas on it" while we're carefully working on our fire preparations. However, after doing a Winter survival course with Mors, I realized my fire-lighting skills had actually been pretty basic.

Mors' carefully detailed explanation of how to carve "feather sticks" goes far beyond the chubby and blunt-looking "fuzz sticks" diagramed in the old BSA handbooks. While I was somewhat familiar with the concept of the feather stick, I'd never seen someone make a massive, bound, tinder bundle like Mors. He snaps off an armload of full-length dead spruce boughs, folds them over once, and quickly binds them with a flexible twig into something resembling a large twig football (Photos below). He lights the bundle while holding it at waist level, and the bundle quickly burns into a hot torch that is easily controlled and manipulated by hand, up off the cold, wet ground. The bundle can be lit while sheltered from wind and rain, and it can easily be waived for oxygen, as opposed to kneeling and blowing. The Kochanski-style tinder bundle is a true life saver!

That's really just the beginning of the fireworks show. Mors taught flint and steel fire lighting, use of the bow drill, hand drill, and how to source and locate numerous natural tinders and fire materials. He teaches special fire lays for all night fires and for burning on top of deep snow. His work in this area—especially for the northern coniferous forest—is exceptional and should be studied by everyone who walks these woods!

8. Real Gear and Full-sized Tools

Mors while show you how to live in the woods with the bare minimum of equipment, but it's a different approach the ultra-light backpacking proponent. Actually, I bet most lightweight hikers and Leave No Trace followers would recoil at Mors' knife and axe recommendations. Mors' goal is to teach you how to survive in severe cold, and that requires real tools capable of doing real work with minimum effort. So, when you hear him say that you need "A saw capable of felling hug-sized trees," he's not kidding. In fact, he stresses not relying on wire saws and razor blades when trying to survive in a northern Winter. The cold is not forgiving, and you are working against time to secure your survival situation.

9. Be Prepared!

Mors is famous for saying "the more you know, the less you carry" or "knowledge weighs nothing." With Mors' skill and knowledge, and assuming that he was able bodied, he could likely get by for quite a while just using resources from use his natural surroundings. However, Mors is also a realist, which means he's a big advocate of carrying a well prepared survival kit. A survival kit is not a new concept, but Mors has written booklets on the subject, again, with very specific recommendations for boreal forest survival, among other items: adequate clothing, a proper bush knife, a pot, and the "Magic three of modern survival", which includes a ferrocerium "ferro" rod (or in Mors speak, a zirconium rod), 7-strand paracord, and mylar space blankets. These compact components will help you combat dehydration, stay warm, and build shelter.

10. Jam Knot

Arbor knot (Canadian Jam knot)

I enjoy learning how to tie knots and work with rope. It's fun in a problem solving way, but what I really love about knots is the satisfaction I get from rigging up a taut fly on a rainy day, effectively hanging a bear bag when there doesn't appear to be an easy solution, or lashing together a useful camp project . Knots can be tricky, but knowing the right one to use, and how to use it can make a world of difference in the wild.

Here again, though, Mors showed me something new: the "Jam Knot" (aka Arbor Knot). This knot uses little cord, cinches up powerfully tight with paracord, and has a million uses. In a survival situation, it is particularly useful for binding two shelter poles together while using far less cord than standard lashings.

A Mentor Like No Other

Mors' knowledge and experience is legendary! Using a lifetime of in-the-woods learning, he teaches people the intricate details of practical survival skills he's adopted or developed for his boreal forest environment. HIs affable personality and approachable teaching style make his courses even more enjoyable. Today, with digital technology, Mors' reach continues to grow. It's virtually impossible to participate in an online survival discussion without having Mors' name and teachings come up, and more and more, I'm meeting people who've taken classes from or worked with Mors. There's also getting to be quite a few highly-skilled instructors who've learned and are now passing on Mors' techniques. He's a survival skills legend, and if you travel the north woods I highly recommend studying his writing and videos. And, if have the chance to learn from him in person, do it!

Keeping your hands warm in the frigid cold is important for fun Winter outdoor adventures. Check out our tips and advice for warm hands in all Winter weather!