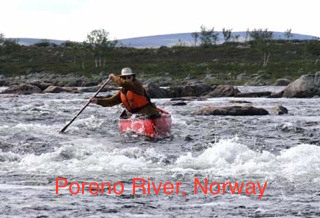

Cliff Jacobson teaching proper canoe handling technique during the BWCA skills prep workshop.

Cliff Jacobson has been a great mentor to me for years. I first saw Cliff speak at Canoecopia in the early '80s. Cliff is a master storyteller, so even though I was a fairly young, Cliff's presentation really kept my attention. When my dad later picked up a copy of Cliff's book, Canoeing Wild Rivers, I soaked up the skills and techniques Cliff outlined to improve my camping skills. As years went by, I read all of his books (no small feat!) and attended Cliff's speaking events at the big wilderness and outdoor symposiums, where he consistently provided rock-solid and entertaining advice.

I got to know Cliff on a personal level through the Boy Scouts of America (“BSA”) when I had the honor of working with him for a few years on the Expedition Canoeing School that raised money for college scholarships for Eagle Scouts. I promoted the event and managed logistics for the weekend-long workshop, while Cliff provided invaluable knowledge and hands-on skill development for anyone taking a trip to the BWCA or deep into the Canadian wilderness. It was a fantastic event for a great cause, and I'll always be indebted to Cliff for agreeing to donate his time and knowledge to the BSA for so many years.

One of the things I really like about Cliff is the fact that he's a pragmatic guide. He emphasizes developing skills and judgement over buying all the latest and greatest gear, yet he has some very detailed gear recommendations for serious trips. His style is a mix of old and new with the consistent factor being confidence in his approach.

I recently caught up with Cliff to talk BSA, camping, canoeing, adventures, and, of course, books.

Leading Group Canoe Trips

What's your advice to a scout leader if their unit wants to run a high-adventure trip on a wild river? Is there a progression of trips you’d recommend to build experience? Do you think there's a minimum age for a youth group trip on more advanced rivers, like the Kopka or Bloodvein Rivers? A leader to scout ratio? Are skills or training outside of BSA needed?

At the outset, I can’t think of anything more wonderful than taking a bunch of qualified Scouts on a canoe trip down a wild river. Here’s my advice to the lucky, prospective Scouters:

1. Read everything you can find about canoeing and camping. Don’t overlook books written in the early part of the century. Yes, equipment and, to some extent, methods have changed, but the judgment skills for safe travel remains the same.

2. Take a whitewater canoeing class. Be sure to specify that you want to learn Canadian-style canoeing, not “sport boating.” Emphasize that you want to take your training in a standard 17-foot expedition-style tripping canoe, and you want to become proficient in back ferries, forward ferries, eddy turns, and peel-outs.

3. Once you have the essential paddling skills, you’re ready to train your troop. Here’s the procedure I followed when I trained my group of teens to run Ontario’s English, Steel, Kopka, and Gull Rivers (the Gull River is very technical—hardly anyone canoes it):

One Saturday was spent on a large local pond. Kids were assigned positions—bow or stern—and no switching was allowed. This seems cruel, but it’s important because the development of muscle memory depends on doing the same thing again and again, without hesitation. Switching positions puts the ball in a new park. Now, if this same group of kids were to canoe another river the following year, I would make some adjustments and let them change positions. Again, they would have to stay in those positions until muscle memory was perfect. You just can’t be in the middle of a tough rapid where an instant draw or brace is required and have someone do it incorrectly. Your responsibility is to get your crew safely downstream.

Strokes taught included: bow (draw, cross draw, high-brace) and stern (draw, pry, low-brace). Teams paddle (coordinate) backward together around a bleach jug obstacle course. They must do this WITHOUT talking to one another. This means that each partner must know exactly what stroke will move the boat which way. It’s quite impressive to watch them do it.The following Saturday, we canoed the Kinnickinnic River near River Falls, WI. It’s an easy river with Class I and low Class II rapids, but it moves along quickly and is virtually all current for 10 miles from Glen Park in River Falls to the State Park near Hwy FF. Here, we practice back ferries and forward ferries repeatedly—even in places where a simple turn will work—to emphasize perfection of style.

Trip three was on Minnesota’s Snake River, which has some real Class II rapids that can be fairly technical, depending on water levels. Again, we practiced ferries, eddy turns, peel-outs, and added side-slips.

At that point, we were ready to go canoeing! My first trip with the kids was on Ontario’s English River. We went in by train from Ignace and paddled out, getting a shuttle from Cozy Creek Campground near Barrel Lake Provincial Park. There were many portages (the longest was nearly three miles down an old logging road) and some pretty big rapids, too. I was paddling a Mad River TW Special at the time, and it was a bear to get around in the tight rapids. About two-thirds of this crew would go on to canoe the Steel River the following year, then the Kopka (we flew in by float plane), and lastly, the Gull.

I should point out that in all my trips with teens, there was never a capsize on the river, and we paddled some pretty dicey stuff. These kids were so well programmed that whenever they saw dancing waves ahead, they immediately went into back ferry position, slowed the canoe, and moved sideways into a dedicated flow. It was quite remarkable.

Many of our readers are volunteer or professional outdoor leaders and many aspire to be in such positions. What are the different requirements as far as skill, preparation, and mindset between someone who is proficient with their individual wilderness skills and travel, and a wilderness guide? Or the difference between a guide and an instructor?

As I see it, the big difference between someone who has great skills and one who is a guide is simply responsibility. You really look at things differently when you’re guiding a group. As a guide, your most important task is to care for the group, especially the weakest member of the group. You’re constantly jockeying to make everyone comfortable and happy, and your own comfort comes last.

Cliff Jacobson teaching skills for a successful BWCA canoeing adventure.

I remember one night on the Caribou River in Manitoba when we pulled in at 10:00 p.m. after canoeing 18 hours. There were no satellite phones in those days, and our float plane was going to meet us at 8:00 a.m. the following day. We had lost three days crossing Hyde Lake, due to incessant rain and high wind. Everyone was dog-tired. A friend who was on the trip and I prepared supper while everyone else huddled inside their tent away from the bugs. We brought food to everyone in their tents. My friend and I ate last, under the tarp, around midnight. As the guide, you always have to be first up in the morning, last in bed at night, and always have your thumb on everything.

Instructor simply means “one who instructs.” With due respect, there are “wilderness skills instructors” in Scouting who know very little. The problem is they think that everything about the wild outdoors is in the Scout manual, and ways that differ are either wrong or anti-environmental. Yes, there’s a lot of great stuff in the Scouting manual, but there’s also a lot missing. And frankly, the majority of recommendations concerning camping, canoeing, wilderness travel, and related stuff are more geared to state park and camporee-style camping than to the deep outback. That’s probably as it should be. BUT, if you want to go well beyond the beaten path and guide trips there, it's best to look well beyond the skills that Scouting has to offer. Heed the advice of those who have been there and done that and have come home smiling. And don’t be surprised if some of what they tell you clashes with common Scouting views. Examples like “don’t carry garbage on your back in bear country—especially, grizzly country," "do bring serious tools to build a fire—fixed blade knife, hand axe, folding saw," "don’t put your food pack in a tree in bear country because black bears climb trees"—believe it! (The only thing you accomplish by treeing your food is to keep it away from you. The bear will get it and hopefully, not you.)

Mindset may be the determining factor in the success of a guide and/or skilled traveler. Before the days of satellite phones (when you couldn’t quit in the middle of a trip), campers learned to just suck up bad times and keep going because you had to be where you planned to be or you missed your charter float plane. Those old days built character. Everyone needs to learn that you can’t just quit when things get tough. Indeed, I would offer that a no-quit mindset may, under certain conditions, even trump good skills. Mediocre skills, a willingness to learn, an open mind, and a heart to keep going more often than not will spell success. But weenie out and the best skills may not be enough.

Practical Approach to Outdoor Adventures

You are a Distinguished Eagle Scout, trained in forestry, with a long career as an Environmental Science Teacher and wilderness guide. Leave No Trace (“LNT”) principle number five, “Minimize Campfire Impacts,” has been interpreted by many organizations to mean “no fires.” LNT further states that one should “only use sticks from the ground that can be broken by hand.” I’m in complete support of being a safe and clean camper, but it seems LNT is being misinterpreted and misapplied in the northwoods environment. Carefully and skillfully using locally-sourced dead wood can have less overall impact than stove canisters and fuel, and campers are missing out on developing an ancient skill that could be a lifesaver. And who doesn’t feel a deep soulful experience when quietly staring into a fire while on the banks of a wilderness lake or river? Am I way off here? What are your guidelines for fire practices on your trips? Do they vary based on location?

I have deep respect for Scouting; it made me who I am. Still, not all the advice in the Scout Fieldbook and Handbook is sound. In fact, I think the Scouts need to take a more realistic look at some of their backcountry policies. The Scouts and the Federal government seem to share one thing in common: they believe what’s best for one wilderness area is best for all, and that is simply wrong. What’s best when canoeing the Green River in Utah is not necessarily best for the BWCA. No effort is made to distinguish between the requirements of different ecosystems. There is nothing wrong with campfires; indeed, camping without one is a wanting experience.

Regarding the LNT practices, in the BWCA, for example, there’s plenty of dead downed wood. It grows much faster than the quarter million people who canoe there every year can possibly burn. Yes, the campsites are pretty bare, but not because there’s not enough wood; it's because most campers are too lazy to take a short walk into the woods where they’ll find hundreds of dead downed trees. There simply aren’t enough dead branches in BWCA campsites to satisfy the needs of campers. The tiny sticks burn quickly then, out of frustration, campers try burning green branches, birch bark, cedar foliage, you name it. Better they should walk back in the woods and cut off a dead, downed tree limb. Then, they’ll have a cheery fire for days.

Similarly, the “carry out your trash under all circumstances” policy needs to be reexamined. It can be very dangerous in bear country. Once a dried food pack is opened, food that remains on the plastic will absorb moisture and begin to smell. If you’re carrying that smelly plastic in your pack and there’s a hungry bear around the bend…well, need I say more? Be aware there is no such thing as an absolutely odor-proof bag. Sure, some types come close, but close enough is not good enough. The Scouts are treading on dangerous ground when they encourage groups to carry out food wrappings in bear country. The smart alternative is to burn them. And this hogwash about the plastic polluting the air can’t compare to the pollution that resulted from driving your van from Chicago to the BWCA. This is selective environmentalism.

UPDATE: Cliff recently published a great blog post about practical and common sense approaches to tackling a canoe camping trip in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (“BWCAW”). It’s a fun and great read for seasoned and new canoeists who are heading into the BWCAW.

Survival: A State of Mind

Some people are obsessed with the idea of "survival" today. You've spent thousands of nights in and travelled thousands of miles through true wilderness areas. Throughout your travels, have you experienced anything that would fall into the “survival” category? If so, how did you handle the situation(s)?

Yep, when I was 21-years-old and working for the BLM in western Oregon, I became totally lost while changing the perimeter of a timber sale. I had a Silva compass, a pocket knife, Thermos of coffee, Zippo lighter, my lunch, and a map in my head (no paper map). I knew that if I headed due west, I would hit Hwy 101 eventually. I figured 3-4 days, max. Two and a half days later, I walked into the sunlight of a recently logged area, followed a logging road to the town of Remote, Oregon, where I hitched a ride (over the mountain!) on a logging truck back to my Jeep, which was on the other side of the mountain about 40 miles away. I drove home and never told a soul. Why? Because foresters don’t get lost! Survival is a state of mind. Knowing that I could find my way out was what kept me calm. Today, we call it PMA or positive mental attitude, and it’s worth more than any commercial “survival kit” on the planet.

Writing and Presenting to Audiences Around the World

You’re a prolific outdoor writer. Do you stick to a strict writing schedule or simply write when inspiration strikes? Any advice for aspiring writers?

In the early days, I had a strict writing schedule. I taught school during the week, so I would generally write for three hours each night and all day on either Saturday or Sunday. During Spring and Christmas vacations, I would try to write for about six hours each day. I learned early that it was pointless to write for less than two hours—sometimes it would take me an hour just to get my thoughts together before I hit the keys on the typewriter (yes, we had typewriters in those days!).

A sampling of the books Cliff Jacobson has written throughout the years, detailing his canoeing experience and lessons. The pack pictured above is the Frost River Cliff Jacobson pack, designed by Cliff for Frost River--a great bag for canoeing or hiking adventures.

I think a major reason why I never did very well in English in school is because the teacher would give us 45 minutes to write about some boring subject, which she defined. I would start writing about the last 15 minutes of the period, so I never finished anything. And what I really wanted to write about was camping and canoeing and guns and knives (I used to draw guns and knives in class; heck, today they would probably put me away in some juvie institution for that!). I loved shooting and hunting; I never wanted to hurt anyone, I just liked guns, but the teacher wouldn’t let me write about them. I’ve learned over the years, you must have passion for your subject in order to write well.

Other than your own, of course, do you have any favorite books on canoeing, camping, and wilderness skills that you find yourself going back to again and again?

Oh yes, I’ve read all the works by Calvin Rutstrum, not once, but many times. I also enjoy the complete works of Horace Kephart and Nessmuk (George Washington Sears). These are classics and will never go out of date. I also rather enjoyed The Complete Wilderness Paddler by Rugge and Davidson, although frankly, I disapprove of some of their methods. I would also recommend Father, Daughter, Canoe by Rob Kesselring. For skills, Bill Mason’s Path of the Paddle and Gary McGuffin’s Paddle Your Own Canoe are the supreme texts for learning paddling moves.

I’ve seen you give some of the same presentations multiple times, and they’re always entertaining. You pack the room at Canoecopia, Midwest Mountaineering, and at other outdoor shows. Do your presentation skills come from years of teaching? Any tips for giving a great presentation?

Well, I was a teacher for 34 years, and as every successful teacher will attest, you can’t teach ‘em if they ain’t listening! This means that you must be an entertainer. Good teaching—at least at the elementary through high school level—requires a lot of preparation. It’s a lot like acting: you paint on a smile and go for it with all your heart. It’s quite exhausting. Teachers have necessarily learned the skills to keep an audience smiling. If kids don’t pay attention, they won’t learn. Most of the job of teaching is keeping their attention—and that often requires detracting from the in-stone curriculum to provide current things that kids need to know right now, not the pie in the sky time when they’re in college. This is a very real problem for teachers and presenters everywhere. Often, one has to teach very dry stuff that is not appealing to students. Fine, do it, but not for too long. Intersperse jokes and diversion, then come back to the rigor.

Boy Scouts of America

Since we’re taking a BSA bent on this post and talking about the Expedition Canoeing School, do you have any thoughts you'd like to share on Scouting, your experience with Scouting, or the value of Scouting?

I meant it when I said that Scouting has made me who I am today. Admittedly, things were a bit wilder when I was a kid compared to now. We didn’t have all the rules that we have now. No one even thought about liability in those days. When I was 12, I was on a Winter trip where one of the kids in our troop was killed while sliding down a slope near Iron River, MI. We were all tobogganing down that slope using a medical stretcher (it folded up). We tied crossbars to it to keep it from folding. The crossbars broke and the stretcher slammed into a tree. The boy was killed instantly. I don’t know what became of that, but somehow, it was accepted as a simple accident. Today, there would be multiple lawsuits. Also, in those days (the early '50s), when you got your totenchip, no one hassled you about carrying a sheath knife or hatchet. Today, many in the BSA discourage fixed-blade knives and axes of any kind. Some years ago, there was a section in one of the Scout books that incorrectly showed how to sharpen a knife—the edge was pulled away from the stone not towards it. The idea was that it was safer to do it that way. Safer, yes. Wrong, absolutely! You don’t teach someone to do something incorrectly just because it may result in fewer accidents. I see that incorrect procedure has been removed from the Scout book today.

Cliff Jacobson's latest book, Canoeing Wild Rivers.

On a positive note, I believe that things are changing for the better in Scouting. Now, you can have a fixed-blade knife and a hand-axe on your trips. And the correct sharpening method is illustrated. Open campfires are now considered acceptable practice in many places; it is not as heavily discouraged as before. We do continue to struggle with liability problems, but fortunately, most Scouters keep a stiff upper lip and take their troops adventure camping without much worry. If we take liability too seriously, then best just give every Scout an iPhone and send him home.

If you want to see a real liability mess, check out the Girl Scouts. Some years ago, before the Venture program was in place, two eighth grade girls asked to join my troop. “Why not join Girl Scouts?” I asked. “Because all they want to do is sew and sing; we want to go camping!” And that says it all and is why so many young women are joining Venture crews.

On a final note here, I do want to add that if you show me 100 Eagle Scouts, I’ll show you 100 rather incredible young men. Compare them to any 100 non-Scouts of the same age and there’ll be no contest. If I had my way, I would open the entire Scouting movement to girls, starting at age eight in the Cubs. They would go through the exact same program as the boys, ultimately earning Eagle. I think that’s the direction Scouting should take.

If you want to know more about Cliff, check out his website, or pick up the updated version of his flagship book, Canoeing Wild Rivers, on Amazon!